The plea for immediate action to introduce stronger state backstops comes amid signs European finance ministers will reject a proposal for joint guarantees for long-term bank debt, fearing it would leave taxpayers in richer countries too exposed.

A watered-down version of the plan, to be discussed at a gathering of ministers on Wednesday, will involve national governments continuing to underwrite bank bonds, as around 15 European Union countries have done since 2008, while coordinating more closely on the exact terms and levels of fees. Since the summer many banks have effectively been shut out of funding markets because of the sovereign debt crisis, a trend that is likely to make many institutions reliant once again on state support to attract investors. Almost a third of euro-denominated bank bonds sold in the first quarter of 2009 were backed by state guarantees and a big portion of this debt is expiring, with bonds worth about €140bn maturing next year, according to Dealogic. In a letter arguing that national schemes alone will be insufficient to meet these funding requirements, a group of finance experts advising the European Banking Authority are calling on government’s to reconsider and “urgently adopt a European approach”. “Given that so many sovereigns are themselves unable to borrow at sustainable rates this national level approach will not work at this time,” the experts wrote, in a letter to finance ministers.

“The interconnectedness of the EU banking system is so high that the inability of banks in troubled countries to fund and recapitalise themselves through the markets is weighing all EU banks down.”

The letter is signed by the six academics and think-tank members on the EBA’s banking stakeholder group, including Daniel Gros of the Centre for European Policy Studies, Rudi Vander Vennet of Ghent university and Sony Kapoor of Re-Define. Germany has led opposition to the idea of “joint syndicates” to underwrite bonds, arguing the proposals would make German taxpayers liable for hundreds of billions of bank debt, mostly in peripheral eurozone economies. The European Commission is expected in coming days to adjust its state aid rules to account for the creditworthiness of countries offering guarantees, so that banks pay smaller fees to buy guarantees from governments with weaker credit ratings. However the tweak to the fee rules may be too little to make some national guarantee schemes workable, given the painfully high borrowing rates faced by some eurozone countries. Some funding strains could be alleviated through more action by the European Central Bank, which is considering steps to make it easier for banks to obtain its liquidity by broadening the range of assets it accepts as collateral. The ECB may also offer banks loans lasting as long as two or three years. Such moves, the ECB’s equivalent to “quantitative easing”, would be in addition to an already announced offer of 13-month liquidity in December.

Eurozone bank lending to the private sector accelerated last month, providing unexpected relief for the ECB as it mulls fresh action to prevent financial sector weaknesses pushing the region deeper into recession.

However, the pace of growth remained modest by historic standards, hid regional variations and did little to dispel fears that eurozone banks’ shrinking balance sheets and funding difficulties could severely restrict the flow of credit to the real economy in coming weeks and months – in turn, hitting economic activity.

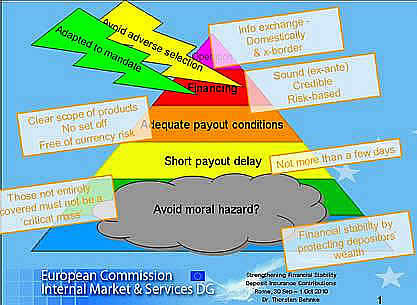

When the financial crisis hit, the colossal failure of some DGS to honour and manage depositors’ national and cross-border claims led to major government interventions. To alleviate the pressures, the EU decided in the midst of the crisis to increase the minimum coverage to € 50,000 and later € 100,000, but left the remainder of deficiencies to be addressed in a more elaborate proposal.

|

|

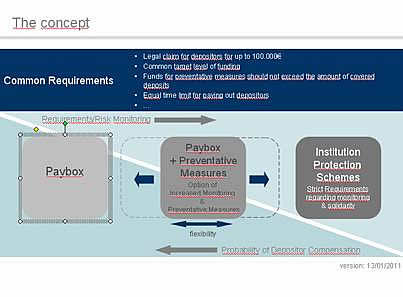

The Commission’s proposal, issued last summer on July 12th, addresses some of these challenges. It fixes the coverage level at €100,000, extends insurance to all currencies, lays down financing requirements, some ex ante some ex post, enables cross-border borrowing amongst DGS in case of insufficient funding and establishes report obligations to the newly created European Banking Authority. The proposal goes too far for some, as it entails important adaptation requirements of national systems that had different scopes of coverage or funding mechanisms in place. At the same time, it falls short of expectations for others, as it basically keeps the current structure of national DGS and does not adequately address existing challenges. The text does not touch upon governance issues, legal structures or ultimate liability (public/private) in case of bank failure.

The question thus arises how to design a scheme for the single market. Should deposit insurance be integrated into an EU financial safety net? Should there be another form of a pan-European scheme, possibly a 28th regime or a single fund? Taking these questions as a point of departure, speakers assessed the Commission’s proposal and share their insights on remaining problematic issues.

The link between deposit insurance and bank resolution is missing. Possible consequences are depositors panic, destruction of lending relationship, domino problem (contagion throughout payment system) and moral hazard risk. Putting the link together, it delivers a resolution tool and contributes to early intervention. Also debt-equity conversion, living wills, separating critical fractions from other parts of institutions can contribute to stability within the globalized financial system in order to decrease outcome of 'type 1 and type 2 errors'.

Furthermore, a supranational supervisor was plead for. Discussed was also the number of matrixes: one scheme for pan-Europe or a scheme for member states countries and apart from that for the other states in Europe.

Anyway, aim is to protect the system (not institutions, shareholders). There is need for legislative convergence, within the EU as well as international (Basel III, IADI). The role lender of last resort, DIS and laws concerning insolvency should be gathered up together. DIS allows public authorities to close banks more easily.

Argueing, it can also be said that a deposit insurance scheme is a recept for trouble and really a good cause. During uncertain times disadvantages fall into the background. In normal times, however, there is talk of moral hazard. A scheme puts up wrong behaviour amoung depositors and financial institutions. Depositors will have no stimulus to pay attention at which financial institution they put the money, because thinking is not necessary anymore. After all, their risk disappeared and shifted to the guaranteeing financial institutions and eventually to the taxpayer. A scheme is also an invitation for excessive risk taking financial institutions to enter the savings-market. Such institutions offer high rates by investing the money in risky loans and investments

Having thought of it that way, a scheme will undermine financial stability. IMF and the World bank researched the efficiency and pointed out a destabilized effects. Arranging a fund in advance and risk related fees is semblance.

To clarify a new bail-in doctrine, created because of the troubles of Cyprus, P. de Grauwe drafted April 2013 in the commentary 'A recipe for banking crises

and depression in the eurozone' issues, items and recommendations on this subject. The most significant effect of the Cypriot crisis is that the rules governing the

resolution of future banking crises in the eurozone have been rewritten. According to

the new bail-in doctrine future bailout operations

will involve deposit holders. Those who hold deposits of more than €100,000 now know that

if their country gets into financial trouble and has to ask for support from other eurozone

countries, they are likely to lose part or all of their savings.

The new template guiding the resolution of future financial crises will have negative

consequences, on two counts; it increases the systemic risk and makes future bank crisis more likely and it will impose large economic costs on countries subjected to the bail-in treatment. To reduce the moral hazard risk, the regulation of

banks should go much further than what has been achieved today. The imposition of tighter

regulation, including much higher capital ratios; a separation of investment banking and

commercial banking; and caps on time-deposit interest rates is a better approach than the

bail-in option, which will have enormous economic consequences for the countries of the

eurozone that have transferred much of their sovereignty to the creditor nations in the north

of the eurozone. |

|

Another starting point is implementing severe requirements at the gateway and strict monitoring afterwards. This secures a good look can be given after business models: next to solvency and liquidity it is also the nature and quality of the loans and investments. A financial institution is important as public utility and therefore it has to do with little market operation.

For a comprehensive report please see ECRI POLICY BRIEF NO. 4 (MARCH 2011). Conclusion and recommendations from this report:

Sixteen years after the first EU legislation, the

challenge to harmonise deposit protection schemes

remains. During the crisis, a number of DGS proved

unreliable and serious cross-border tensions emerged

in handling payouts. As a result, increasing the

efficiency of deposit protection schemes emerged as a

policy priority. But to what extent should schemes be

harmonised in the EU and what roles should they

have?

The Commission’s 2010 proposal is a first step

forward, covering a number of aspects of DGS, such

as the harmonisation of scope of coverage and

deposit/depositor eligibility. This will increase

consumer protection in many countries and limit

incentives to locate savings in markets with higher coverage levels, as the same amounts and types of

deposits will be insured throughout the EU.

The proposed financing requirements and targeted

fund size of deposit insurance are necessary, because

past experience has demonstrated that the fund

availability was not sufficient to handle consumers’

claims following bank failures. The target level of

1.5% of eligible deposits appears reasonable, as

experiences have been positive in the US with the

FDIC target level at 1.15-1.5% of insured deposits.

But it implies that several DGS have to change from

ex post to ex ante funding and have to create

considerable reserves. This comes at a high cost for

credit institutions, in addition to the new standards for

capital and liquidity requirements stemming from

Basel III, and possibly other rules.

While the Commission’s proposal certainly has its

merits, a number of issues are left open, for example

what further roles deposit insurers should take on. As

argued above, there are strong reasons to equip

deposit insurers with a mandate beyond the simple

pay box function, and including them in the wider

financial safety net. If that role was extended to

intervention measures, European DGS would need to be equipped with adequate powers and tools. Such

mandate would only make sense if banks’ resolution

procedures were clearly aligned as well. DGS should

be assigned a clear role in the European stability

framework; limited reporting requirements to the

EBA is not sufficient. And their role should be

reconsidered now, as the regulatory response to the

crisis should embrace the entire safety net in order to

avoid any inconsistencies.

An important omission in the Commission’s proposal

is governance structures and the ultimate liability of

private and public DGS. Would it be better to have a

pan-European scheme administered by the public or

private sector? For the time being, both governance

structures exist at the national level. Yet, no matter

how well a DGS is designed, there always remains an

implicit responsibility on governments to step in as

the lender of last resort, as was largely the case during

the crisis. This ultimate liability of the public sector is

a strong argument in favour of publicly administered

pre-funded deposit insurance.

Out of the three possible pan-European schemes

discussed above, the only efficient, reliable and

sustainable solution is full harmonisation, meaning

the creation of a single European deposit insurance

scheme. The network structure always leaves

regulatory gaps, as does a 28th regime. With full

harmonisation, many challenges posed by the existing

variety in national deposit insurance schemes would

disappear, for instance related to the scope of

coverage, payout procedures and – most important –

the branch vs subsidiary treatment of foreign banks.

For the time being, however, full harmonisation is

difficult to enforce, as some member states and

national interest groups are already manifesting their

dissent over the Commission proposal.

Pleas by national governments and interest groups

that stronger harmonisation of deposit insurance is not

in line with the subsidiarity principle can be

disregarded, as DGS of a different nature cannot coexistcoexist

in a single market and European action to

address deposit insurance challenges is more effective

than action taken at national or local level. The

problems that have arisen to protect and reimburse

depositors across borders call for more harmonisation,

since a network approach is clearly insufficient. |